“The Big Short” is a film about the 2007 US housing market crisis which according to the US Federal Reserve cost the global economy about $10 trillion. In the UK it’s estimated that the Government spent £123.93 billion propping up the economy. It resulted in millions of people losing their jobs and homes worldwide.

What the film shows all too graphically is not just the greed, incompetence and the barefaced corruption of many of the people working in the investment banking sector but that after such a catastrophic failure all of the people responsible for the crisis escaped any of the consequences for their actions. The film’s final image shows a picture of Mr. Kareem Serageldin, a mid-level functionary from a tier-two financial institution, who was sentenced to 30 months in prison for crimes related to the housing crisis. Members can draw their own conclusions about why Mr. Serageldin was the only person to receive a prison sentence? One of the morals of the story is that those who deserve punishment get away with it and it’s usually the little people who are left holding the can.

Now, fast forward to TSB’s IT disaster and we have the same morality tale. TSB is engaged in a witch hunt against those members of staff who complained when the meltdown hit 1.9 million customers. It was inevitable that some of those customers who were affected by the meltdown were also TSB staff. But let’s be clear, TSB staff who are also customers of the bank have the same rights as other customers and their complaints should be treated in exactly the same way. What’s interesting is that the witch hunt started just after Debbie Crosbie, Chief Executive, started her new job. Coincidence? We think not.

The bank is arguing that some of those staff who complained used their knowledge of TSB’s complaint process to secure higher payments. There is no evidence of that in the cases we have seen. Staff were entitled to complain, and it was TSB who determined the size of the payments made to customers.

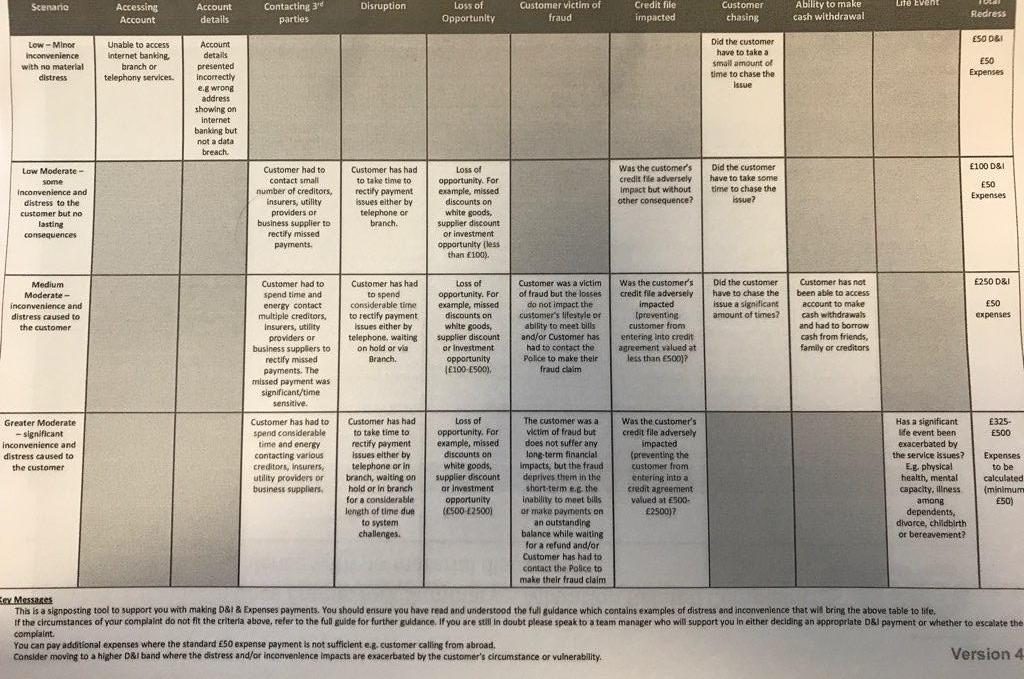

The TSB customer complaints matrix, a copy of which is set out below, is open to such a wide degree of individual interpretation that two customers suffering the same degree of distress and inconvenience could get significantly different payments. So, for example, customers chasing the bank about their accounts were entitled to a payment of between £50 and £250, depending on how often they contacted TSB. What’s the difference between a customer who contacted TSB twice and spent an hour on the phone and another customer who contacted the bank 10 times but also spent an hour on the phone. Arguably, there is no difference but one gets £50 and another get £250. In fact, tens of thousands of TSB customers could argue that they should have received larger payments once they see the matrix. In its rush to scapegoat individual members of staff, TSB has potentially opened Pandora’s box. We received a copy of this matrix a few months ago and decided against highlighting its inconsistencies – to the FCA and Treasury Select Committee who are investigating the TSB meltdown – for fear of causing further damage to the bank from customers complaining that they had been short changed. The bank’s decision to persecute our members means that we have no such compunction now. Equally, TSB needs to understand that we have set up a team of lawyers to review every case and we will protect our members against this witch hunt, no matter what it takes.

And to go back to our original analogy, the real culprits in this sorry saga are those senior executives who were directly responsible for the IT migration and who, like the investment bankers in the “Big Short”, seem to have got away with it leaving the ordinary members of TSB staff to carry the can. Well, not this time!

The short history of TSB since it was spun off from Lloyds has been characterised by poor decision making at almost all levels of senior management. Ms Crosbie needed to get a grip on this organisation’s decision making quickly but this coming debacle is not a good sign. We wait to find out whether she was involved in the decision to persecute staff customers who had the temerity to seek compensation.

For ordinary staff, an obvious question is whether, if they are going to be treated as second class citizens, it now makes sense to have an account with the bank that employs them?

Members with any questions on this newsletter should contact the Union’s Advice Team on 01234 716029 (Choose Option 1).